While companies are digging in for a long winter, executives and politicians fear a wave of deindustrialization

As European businesses brace for energy shortages, workers at one plant in south-eastern France are getting a new winter wardrobe.

Saint-Gobain, the French building materials group, has ordered extra warm coats and gloves for staff at its warehouse in the Alpine town of Chambéry, who have agreed to turn down the heat this winter. In order to cut gas consumption, temperatures will be closer to 8C, instead of the usual 15C.

“It will be just like working outside so we have to give them all the tools to work in an outside environment,” says Benoit d’Iribarne, senior vice-president of manufacturing.

Turning down the thermostat is no mere cost saving for many of Europe’s industrial companies as they dig in for a hard winter. With energy prices soaring to unprecedented highs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it has become a matter of survival.

Europe’s industrial base employs some 35mn people or roughly 15 per cent of the working population. The bloc’s leading industrialists warned earlier this month about the potentially devastating economic impact of the energy crisis.

“Soaring energy prices are currently precipitating an alarming decline in the competitiveness of Europe’s industrial energy consumers,” said the European Round Table for Industry in a letter to Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, and Charles Michel, head of the European Council. Without immediate action to cap prices for energy-intensive companies, “the damage will be irreparable”.

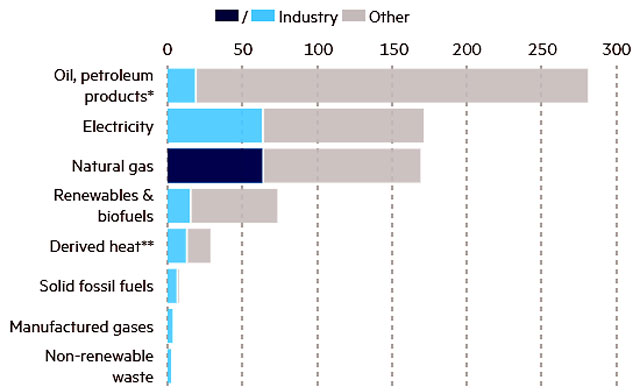

Industry uses more gas than other forms of energy

Total eurozone energy use (million tonnes of oil equivalent), 2019

On the surface, European industrial companies are putting a brave face on it — talking about the energy-saving measures they are implementing and the other costs they are finding to cut. While some are looking to coal and other fossil fuels to get them through the winter, others talk optimistically about the green revolution that the crisis is spurring.

But there is already evidence that major companies are reducing production in some sectors because of the energy shortage, even before the winter kicks in. And executives from chemicals to fertilisers to ceramics warn that they risk losing permanent market share and could be forced to move some of their production to parts of the world that can offer cheaper and more reliable energy.

The alarm bells are ringing among Europe’s politicians. “We are risking a massive deindustrialisation of the European continent,” says Alexander De Croo, Belgium’s prime minister.

Saving energy

In the meantime, companies in sectors from steel to chemicals, ceramics to papermaking, fertilisers to automotives are racing to reduce consumption both to cut crippling energy bills costs and to prepare for gas shortages over the winter, should governments impose rationing.

Many are finding ingenious ways to reduce energy use. French carmaker Renault, for example, is reducing the time it keeps paint hot — a process that accounts for up to 40 per cent of its gas demand.

Such innovations promise to deliver more efficient factories and processes in future. But first, these businesses have to get through the winter.

Those that could do so have increased prices. Cologne-based chemicals company Lanxess, which makes base chemicals and active ingredients for the pharmaceuticals market, increased base prices by up to 35 per cent when energy costs began to surge.

But price increases will not address the problem of gas shortages. Paper and packaging group DS Smith has ordered its factories to cut consumption by 15 per cent, a voluntary reduction agreed by EU member states in July. Machines that used to be idled between production runs will now be turned off, and thermostats turned down. “If we do things like this and turn down the thermostat from 20 to 18.5 degrees we reduce gas consumption significantly,” says Miles Roberts, chief executive.

Valeo, the French automotive supplier, has asked factories to reduce energy consumption by 20 per cent, with measures such as halting production at the weekend and turning down temperatures during the week. Solvay, the Belgian chemicals company, says it is organising its factories to operate on 30 per cent less gas using alternative energy and mobile diesel-fuelled boilers.

Gas is the single most important source of energy for Europe’s industrial companies. But gas is also an important feedstock, used in the chemicals and fertiliser industries. In total, industry consumes about 27-28 per cent of the bloc’s total supply, according to Anouk Honoré, deputy director of the gas research programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

European industry’s voracious appetite for gas

Breakdown of EU gas demand, market share, 2019 (%)

But it is not that easy to cut the fuel out of many industrial processes. Roughly 60 per cent of industrial gas consumption is used for high-temperature processes of 500C and above, such as glass-making, cement or ceramics. “For lower temperature processes, there are more options to use renewable energy and heat pumps,” Honoré says.

For that reason some companies are turning to fossil fuels, in a potential setback for the EU’s green transition plans. Bayer, the German pharmaceutical and biotech company, in 2019 announced plans to move entirely to renewable energy. But it has now reactivated coal “just in case” it is unable to meet heat needs for production.

Carmaker Volkswagen is running power plants in Wolfsburg, its largest site, with coal for the next two winters, instead of switching to gas as planned as part of its decarbonisation efforts.

Even for the lower temperature industrial processes, alternatives are unusually scarce at the moment. The summer’s drought has depleted hydropower capacity, while France’s ageing nuclear reactors are unable to meet demand due to protracted shutdowns and maintenance issues.

So some industries, faced with crippling energy prices and softening consumer demand, have decided that the best way to cope is simply to cut production.

Analysts at investment bank Jefferies estimate that close to 10 per cent of Europe’s crude steel capacity has been idled in recent months. ArcelorMittal, Europe’s biggest steelmaker, expects output from its European operations to be 17 per cent lower this quarter compared with last year after it cut production.

Metals trade body Eurometaux says all of the EU’s zinc smelters have had to curtail or even completely halt operation, while the bloc has lost 50 per cent of primary aluminium production. Some 27 per cent of silicon and ferroalloy output has also been mothballed, and 40 per cent of the furnaces, it adds.

The fertiliser sector, which relies on gas as a feedstock to create ammonia, has also been hit, with 70 per cent of capacity offline, according to Fertilizers Europe. Goldman Sachs estimates that 40 per cent of Europe’s chemical industry “is at risk of permanent rationalisation” unless energy prices are contained.

“With the rapid rise in energy prices, we are constantly reviewing our production levels across Europe,” said German chemicals group Covestro in a statement.

The same story is playing out in the plastics, ceramics and other energy-hungry industries. Consultancy Rhodium estimates that just five sectors account for roughly 81 per cent of Europe’s industrial gas demand: chemicals, basic metals such as steel and iron, non-metallic minerals products such as cement and glass, refining and coking, and paper and printing.

In some of these sectors, temporary shutdowns are not only costly; often they are almost impossible to implement without permanently damaging equipment.

Saint-Gobain’s d’Iribarne says the potential for energy reduction is limited in the company’s glass factories, where furnaces have to keep burning to keep the glass from solidifying. “You can’t reduce consumption by 30 per cent because that means you would have to shut down and that would damage the factory. You would need six months to a year to restart.”

Arc International, a French glassware maker, has had to do just that. Normally furnaces at its plant in northern France need to run 24 hours a day, making up about half the factory’s energy usage. Now the company has idled two of nine furnaces, and extended the maintenance period on another two, after gas bills increased almost fourfold this year. The company has also been hit by a sudden downturn in demand for some of its products, says Nicholas Hodler, the chief executive. As a result roughly a third of staff have been put on furlough two days a week.

The widespread shutdowns are raising concerns that the crisis is opening the door to rivals from regions with lower energy costs. “A reduction or halt of the exports, albeit temporary, risks translating into a permanent loss of market share,” says Giovanni Savorani, president of Confindustria Ceramica, the trade body for Italy’s €7.5bn a year ceramics industry.

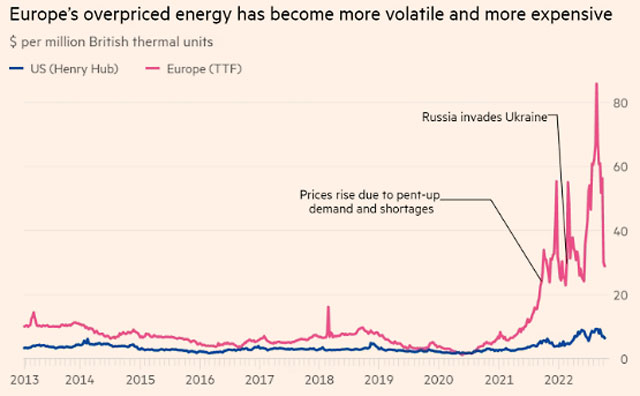

European manufacturers have long complained about the competitive disadvantage posed by the bloc’s fragmented energy market. Over the 10 years to 2020, European gas prices were on average two to three times higher than the US, according to the International Energy Agency.

That gap has widened to as much as 10 times since Russia began cutting back supplies.

“You can import [fertiliser] for half the price we can produce at,” says Jacob Hansen of Fertilizers Europe.

Cefic, the European chemicals industry trade body, points out that since March this year Europe has become a net importer of chemicals by both volume and value for the first time. “This is seriously concerning,” says Marco Mensink, director-general. “We are just way too expensive on a global basis because of energy costs.”

In an effort not to cede ground to competitors, some companies are tapping their lower cost plants outside Europe.

Ilham Kadri, chief executive of Belgium’s Solvay, says the chemicals group could step up production of more energy-intensive products in lower cost markets if needed.

“We are looking at how to prioritise products,” she says “We are a global company and can leverage assets outside Europe to compensate for any reduction in volume there.”

One Italian steel executive says the combination of high energy costs and Europe’s carbon levy is forcing a rethink about where to produce steel, priced at €800 a tonne. “The price of gas used to have a €40 [a tonne] impact, it has now risen to €400,” he says. “If we add the carbon tax on top, the overall impact of energy costs is €600. It makes a lot more sense for us to move production” to Asia.

Packaging groups Smurfit Kappa and DS Smith are both looking to their factories in North America for paper supplies. “We are bringing in more from the US than we have done in the past,” says DS Smith’s Roberts. “To make paper you use a lot of energy. In the US it is much more available and energy costs are much much lower.”

Experts warn that the longer companies are forced to shift production from Europe, the risk rises that some output may never return. Honoré of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies says this happened before.

“When European gas prices were at relatively high levels between 2010 and 2014, we saw relocation to regions with lower prices — such as the Middle East, north Africa and US,” she says. “Industrial gas demand never went back to pre-financial crisis levels.”

“Once investment decisions are made . . . it is hard to ask companies to come back,” says Matthias Berninger, a senior executive at Bayer. “If we were to invest in a new site that has decades long consequences.”

Lower-margin, gas-hungry commodity producers, such as the fertiliser industry, could be among the first victims, suggests Trevor Houser of Rhodium.

“The economics of producing natural-gas-based fertiliser in Europe will be poor for a long time,” he says.

The threat is particularly acute in central and eastern Europe, where many countries have been heavily reliant on Russian gas. Of Europe’s 45mn tons of fertiliser production a year, Poland alone produces 6mn, according to industry sources. All five of its factories are idle. Another 3mn tons of capacity are offline in Hungary, Romania and Croatia. In eastern Europe, 20 per cent of European capacity has been shut down.

Hungary-based fertiliser-maker Nitrogénművek is among those that have had to scale back. Zoltan Bige, chief strategy officer, warns that the implications of capacity reductions this winter could be devastating. “If we do not produce in the summer, the stock does not accumulate,” he says. “Across Europe, there is not the inventory that should be available in the spring when demand starts to increase.”

The lasting impact of the shutdowns across Europe will not be known for many months. But already the reduction in output of chemicals, steel and other critical, basic products is worrying those further down the value chain.

Companies such as Volvo and Bayer have begun to stockpile parts and materials in case suppliers run into trouble. “Our main concern is not the energy price but the availability of inputs we convert into pharmaceuticals,” says Bayer’s Berninger.

The future of Europe’s gas-reliant chemicals industry — and in particular of BASF’s Ludwigshafen site, the largest integrated chemical plant in the world — is deeply concerning for some industrialists. Ludwigshafen is a key supplier to manufacturers of everything from cars to toothpaste and is the engine of Germany’s chemicals sector.

“If the German chemicals industry goes down, three weeks later every supply chain in Europe has a problem,” says Cefic’s Mensink.

Germany’s dominance in the supply chain with industrial giants such as BASF, means that even companies based elsewhere are exposed to the prospect of gas rationing in the country.

“If Germany is not able to supply . . . that will have ripple effect all across Europe,” says Saint-Gobain’s d’Iribarne.

German companies, which account for 27 per cent of the bloc’s sold industrial production by value, are on the frontline. At the beginning of this year, more than 50 per cent of Germany’s gas imports came from Russia and industry accounts for just over a third of demand.

German industry dominates EU gas demand as well as its industrial output

Natural gas demand in manufacturing by EU state, 2019 (bn cubic metres)

Germany also accounts for 27% of EU industrial production*, followed by Italy with 16% and France at 11%

The German government recently unveiled a €200bn support package to offset high energy costs for households and business. But German manufacturers like steelmaker Thyssenkrupp do not rule out the need for drastic action if the crisis continues.

The group has already relocated production away from two of its plants to its flagship site at Duisburg, which runs on its own energy network, and is less reliant on natural gas. The company says it is also prepared to shut down individual plants if energy bills continue to rise.

“The costs of gas and electricity… pose an existential threat to energy-intensive industries such as the steel industry,” Thyssenkrupp says.

Other countries may not have Germany’s industrial heft, but their economies — and employment — are even more reliant on manufacturing. The OECD estimates that Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria and Slovenia, Sweden, Finland and northern Italy have the highest employment shares in vulnerable gas-intensive sectors.

All these countries are scrambling to offer support to their industries and citizens as the weather grows chillier and energy demand rises. But many companies are already looking beyond this winter to the next, and predicting even tougher conditions.

“In 2022, there were decisive volumes from Russian sources,” says Nitrogénművek’s Bige. “If this all goes away, it paints a rather pessimistic picture for next winter [2023-4]. The proportion of new gas sources will increase, but the infrastructure is far from being able to catch up.”

Arc’s Hodler says the scope for increasing prices next year will also be limited. “The real question is whether in 2023 we will see a significant increase in energy costs,” he says. “We are not going to be able to pass on all those extra costs to our customers without seeing a significant impact in volume.”

But there are those who believe the result of the crisis will be a stronger, greener industrial base. Companies such as Saint-Gobain, Solvay and Smurfit Kappa told the Financial Times they were all accelerating energy-transition plans that were in place before Russia’s invasion. Tony Smurfit, chief executive of Smurfit Kappa, says his company is “spending three times what we would have spent” under previous plans. So there are reasons to be optimistic. “This will accelerate the green revolution. Fifty years ago there were no options for green energy and now there are. I think this will make Europe very green.”

Peggy Hollinger in London, Sarah White in Paris, Madeleine Speed in Frankfurt and Marton Dunai in Budapest

Additional reporting by Silvia Sciorilli Borrelli, Sylvia Pfeifer, Alice Hancock, Rafe Uddin, Peter Campbell, Lauly Li

Data visualisation by Chris Campbell

https://www.ft.com/content/75ed449d-e9fd-41de-96bd-c92d316651